Why white notes?

(Creating scales for harmony)

Pianos have white notes and black notes, but the pattern is very irregular. This pattern is very important musically in many parts of the world, and for good reasons. But why that particular pattern?

Elements of Harmony

Previous What are all these circles? (why musical pitch is really two dimensional)

Next Filling up like water (building chords)

Let’s say you are invited to accompany a band. You don’t know in advance what they are going to play or at what pitch, but before each song they allow you to choose just one kettle drum. Kettle drums come with different note names. Which note name should you choose?

The trick is to ask them what the home note of the piece will be. Many pieces have a home note. For example, pieces will often start and finish on that note. If they say the home note is C, then taking into account that this is supposed to be a background accompaniment, not a solo, the most obvious choice for musicians would be a kettle drum tuned to C.

Let’s say the next song has a home note D and you are allowed two different tuned drums. What would be a good choice of two pitches for the two drums? If asked to play an accompanying role, many musicians would likely go for a choice of pitches in the pattern shown below.

Let’s say the next song has home note E, and you are now allowed three kettle drums. A highly popular choice for musicians would almost certainly be the choice shown below. What we are doing here is choosing selections of notes, known as scales, of increasingly bigger size, and we are choosing them for harmonic (playing along with other ) rather than melodic purposes.

Can you see a pattern emerging? For a song with a home note of C and a choice of 4 kettle drums, musicians’ choices would probably vary, as things are getting more interesting, but here is one likely choice.

Each of these choices of a set of pitches is what is called in the trade a ‘scale’. When we get to five notes following the emerging pattern of scooping up notes along the bass players’ circle of fifths diagonal axis (the “dominant axis”), we now hit a world-famous scale, the pentatonic scale. It’s not the specific notes that matter, it’s the pattern. So we can start with any pitch, provided we pick up five pitches on the dominant power bass players axis. So all of these shown below are different pentatonic scales, just starting on different pitches.

Let us keep following the emerging scale building method and extend it to 6 notes. This scale is called Guido’s hexachord and it played an important role in medieval music (for an interesting reason to do with avoiding a problem that is easy to explain in harmony space, as soon as we have learned a little about chord building <see more>)

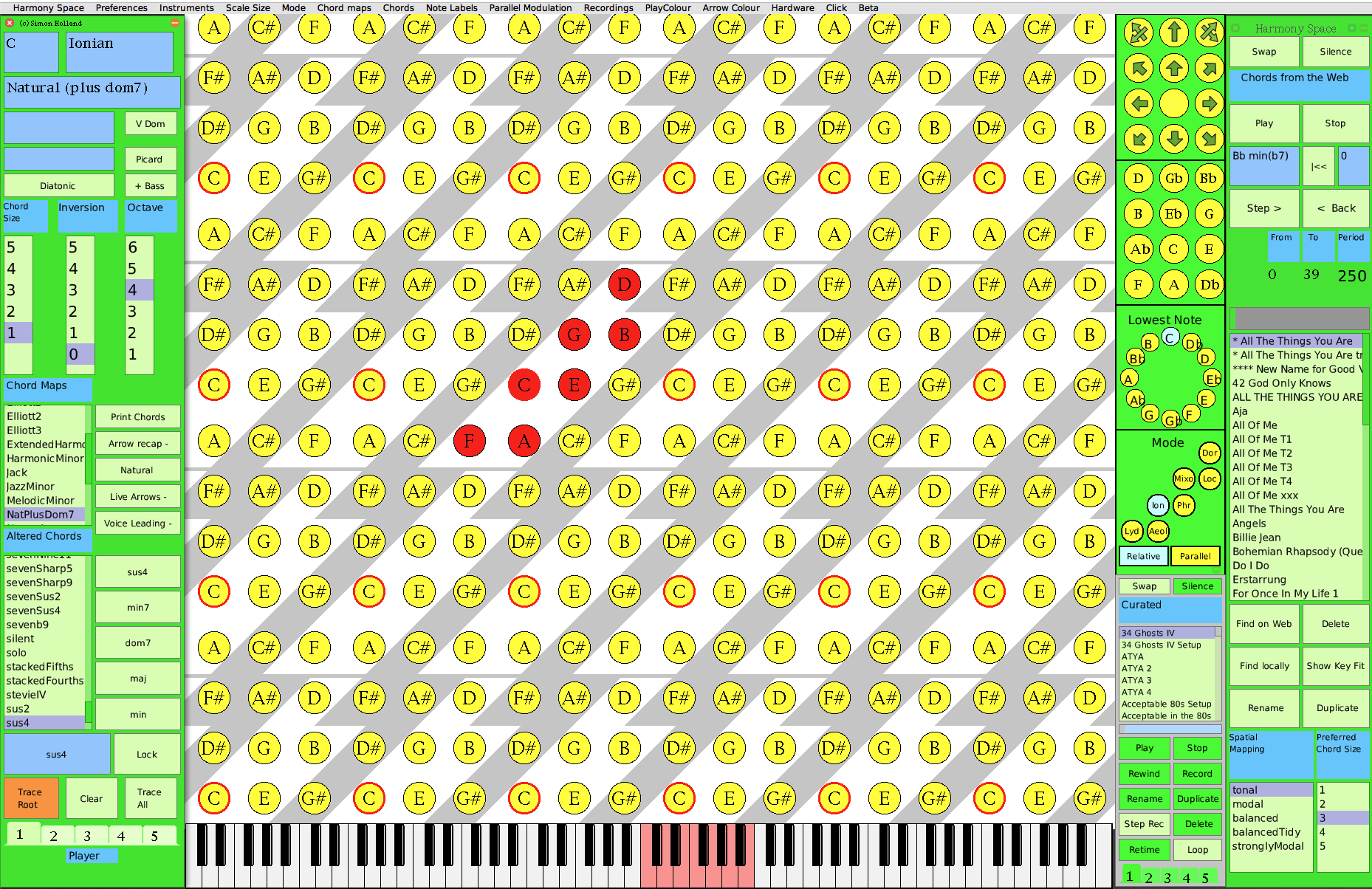

Next here is a scale with seven notes, created using just the same scale building pattern, called the diatonic scale. For reasons that harmony space will allow us to explore in detail, this scale is absolutely packed with structures that will allow us to play all sorts of games to do with movement, trajectory, location, territory, expectation, surprise, and long term structuring - all perceivable more or less by the general untutored listener who has been to music written using this scale. The white notes on the piano fall in exactly this shape. However, again, it is the pattern that counts not the exact notes, so you can make this pattern starting from any pitch, although on the piano you will have to start mixing up black and white notes to play it. In army space, you just use the arrows on the right hand side control panel to move the white area (known as the ‘key window” ) as needed. Thus, these (see illustrations below) are all diatonic scales in harmony space. With just a little exploration we can find out why this scale is so powerful and allows such a variety of games and inexhaustible scope for ingenuity..